在疫情初期,新加坡因能夠有效控制感染人數一度被世界衛生組織稱贊爲“防疫典範”。在二月份時,新加坡曾成功將每日新增的感染人數控制在個位數。世衛總幹事譚德塞甚至評價新加坡的檢測達到”無漏網之魚“的水平。然而自2020年3月底開始,隨著疫情開始大規模爆發,新加坡抗疫的盲點浮出水面:被邊緣化的三十萬客工(外來勞工)。

In the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, Singapore was held up as a role model for its battle against the coronavirus. In the words of WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Singapore’s public health response was “leaving no stone unturned”. By April, however, Singapore’s blind spot became startlingly clear. For all its strengths, Singapore’s government had neglected a community vital, yet peripheral, to Singaporean society – its over 300,000 migrant workers.

新加坡在4月底成爲東南亞確診個案最多的國家。這第二波的爆發主要來源于在擁擠的客工宿舍形成的感染區。(詳見新加坡單日新增首次破百;新增198,累計突破2000 | 客工群體面臨爆發危險)

許多新聞社論評價稱新加坡在疫情初期對客工這一群體的忽視是這次群體性爆發的主要原因。(例如:因忽視抗疫盲點 新加坡付出高昂代價)

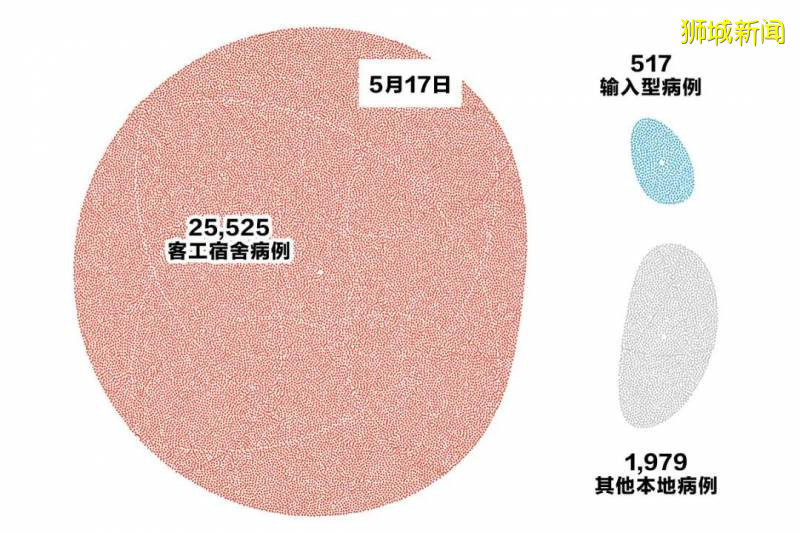

路透網的數據顯示,截至5月17日,客工宿舍的確診人數達到25,525人,占總確診人數的90%。

Singapore was soon struggling to contain an infection spread centred around foreign worker dormitories. After reporting single-digit numbers daily in February, by April Singapore had the highest number of reported COVID-19 infections in Southeast Asia. By May 17, Reuters reported that the number of confirmed cases in foreign worker dormitories had reached 25,535 – 90% of the total.

圖表來自路透社

爲了控制客工宿舍感染的擴大,新加坡政府于四月初成立專門工作小組,旨在加強客工宿舍的防疫措施。采取的措施包括大批量的檢測(每天3千人),將感染區隔離,以及疏散健康的客工、爲他們安排一些更加寬敞的居住場所。然而在這樣的措施之下,客工群體的新增確診人數仍居高不下。截至7月18日,客工宿舍的確診人數達到44,719,占總確診人數的94%。(詳見累計47655|部長提示謹防疫情反撲)

不過檢測的普及度也是這個數字背後的原因之一。7月14日,新加坡衛生部稱已完成21萬人次的客工宿舍人員檢測,占客工宿舍人員總數的三分之二。並預計于8月中旬完成全部客工宿舍人員的檢測。

In early April, Singapore’s government formed an inter-agency task force to, in the words of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, “handle the situation in the dorms”. The task force set up medical facilities and triage clinics, provided food and WiFi for workers stuck in dormitories, isolated infected patients in specially designated facilities, and conducted large-scale testing of up to 3000 persons per day. The high testing rate is undoubtedly a factor, but case numbers in foreign worker dormitories continued to soar. As of 18 July 2020, Singapore has recorded 47,655 cases in a country of about 5.8 million, with 44,906 cases, or 94%, detected in foreign worker dormitories.

新加坡軍醫在客工宿舍建立的檢測點爲一名客工進行檢測(圖片來自網絡)

Here, Army Medical Services personnel attend to a foreign worker at a medical facility set up within the dormitories.

背景聚焦

“客工”或“外籍勞工”這個群體因新加坡疫情的二次爆發而受到關注,只是這個關注來得有點晚。客工指的是哪些人?他們爲什麽來新加坡?他們的生活是什麽樣的?這個星期,我們聚焦新加坡客工面臨的問題和挑戰。

Singapore’s wave of COVID-19 infections has finally drawn the country’s attention to the plight of its migrant labor population, catalysing much-needed reflection from Singapore’s government and its citizens. But who are Singapore’s migrant workers? Why are they needed? How do they live? This week, we spotlight these migrant workers and the myriad challenges they face.

圖片來自網絡

新加坡的客工是誰?

Who Are Singapore’s Migrant Workers?

新加坡客工一般指來自印度、孟加拉國或者中國的低收入工人,他們通過申請工作准證(work permit)來到新加坡,大多從事建築和保潔相關的“髒、累、險”工作,又被稱爲“3D(dirty, dangerous or difficult)”工作。和頒發給所謂高端人才的工作簽證(work visa)不同,工作准證是專門爲從事對技能要求較低的“低端”勞動力設置的,而且對持證者的限制更多:他們不可以帶家人一起來新加坡,只能通過企業申請工作准證,且在持證期間不能變更工作。因爲不能更換工作,雇主若無理剝削,客工也無從伸冤。在這樣不平等的制度之下,客工這一群體在新加坡社會的邊緣化也不足爲奇了。

In Singapore, the term “migrant worker” refers to low-wage laborers who hail largely from India, Bangladesh, and China. They hold Work Permits, a visa category that affords fewer privileges than the work visas given to highly skilled “expatriates”. Work Permit holders are, for example, not allowed to bring family with them to Singapore or to switch jobs, which leaves them vulnerable to abuse and exploitation by their employers. Most of them work in construction or public sanitation, jobs that most Singaporeans characterize as “3D” (dirty, dangerous or difficult). Due to the structural inequalities built into this employment system, migrant workers tend to lead a marginalized existence in Singaporean society.

數據來源:新加坡政府于2019年12月公開的信息

新加坡爲什麽需要客工?

Why Does Singapore Rely on Migrant Workers?

新加坡對客工的需求主要來自這兩個原因:人口問題和勞動力結構的變化。近20年內,新加坡生育率不斷減少,目前已降至1.16%,是全球生育率最低的國家之一。因此本地人口已不足以支撐新加坡經濟的發展。再加上本地人大多接受了良好的教育,對工作比較挑剔,擇業時往往會將“3D工作”排除在外。而幫助新加坡填補這些行業的勞動力缺口的正是客工。換句話說,新加坡向以知識密集型高科技産業和服務業爲主導的“知識型經濟(knowledge-based economy)”的轉型,完全離不開客工。新加坡貿易和工業部2004年的一份研究指出,在1992-1997年新加坡經濟以年平均9.7%的增長率快速發展的時期,客工對經濟增長的貢獻高達29.3%。這個數據或許有些過時,但依然直觀地展示了客工對新加坡的貢獻。

Singapore’s demand for migrant workers is largely fueled by two key drivers: a shrinking domestic population and a local aversion to so-called “3D” jobs. Singapore’s fertility rate has been falling for the past 20 years, and at 1.16% registers as one of the lowest in the world. This has caused Singapore’s already-limited population to shrink, resulting in more job openings than the local population is able to fill alone. Singapore’s economy thus relies heavily on migrant labor, particularly for “3D jobs” that most Singaporeans would refuse to consider. But while jobs in the construction or public sanitation sectors are generally seen as undesirable by Singaporeans, they nevertheless constitute essential functions that support Singapore’s economy. For example, a 2004 survey by the Ministry of Trade and Industry found that between 1992 and 1994, migrant workers’ contribution to Singapore economic growth was almost 30%.

客工在新加坡的境遇如何?

How Are Migrant Workers Treated?

盡管新加坡3D問題的解決以及經濟發展都離不開客工,他們的貢獻並未得到社會的認可,客工群體與本地的社群之間仍然存在巨大的鴻溝。很多新加坡人還是有仇外心理,認爲客工占用了本國人的經濟資源。對客工的不滿甚至在2011年成爲政府選舉的主要政治議題,使得政府對客工設置了更多的限制。時至今日,新加坡人對客工仍然抱有敵意:盡管有70%的新加坡人意識到國內存在勞動力短缺的問題,只有四分之一的人認可客工對國內經濟發展的重要性。

Despite Singapore’s reliance on migrant workers, their relationship with the Singaporean community is tenuous, marred by racism and xenophobia. Discontent with the influx of low-wage migrant laborers was a key issue in the country’s 2011 general election, causing the government to tighten its immigration and foreign labor policies. Even today, Singaporeans are still not open to migrant labor: surveys show that just one in four Singaporeans says there is a need for migrant workers, even though seven in ten agree that there is a labor shortage.

由于無法融入當地社群,客工始終生活在社會的邊緣。2013年12月,新加坡發生了40年來首起客工騷亂事件。騷亂的起因是一名印度籍客工被一輛私人巴士撞倒身亡。這起事故引發了涉及300多名客工的騷亂,進一步激化本地社群對客工的偏見。

Migrant workers do not just face social ostracization – they also live on the physical periphery of the local community. Unfounded concerns about the safety of the elderly, the young, and property devaluation fueled a “not in my backyard” mentality that kept workers on the periphery of local residential estates.

2013年客工騷亂(圖片來自網絡)

受事件影響,新加坡政府采取了爲客工建造宿舍的措施。2014年的政府文件中甚至有“如在宿舍附近設立價格合理的日用品店,客工就可以不需要離開宿舍區域、進入本地居民區(去購買生活用品)”這樣的記錄。似乎認爲只要把客工和本地社群分得夠開,沖突就會減少。很多社會組織和醫療專家都曾對這個治標不治本的計劃提出異議,指出人員密集的宿舍將成爲傳染病的溫床——而七年後的今天,擔憂變成了現實。

In December 2013, the government ordered the construction of additional worker dormitories after some 300 migrant workers rioted following the death of a fellow worker in a bus accident (the first instance of such unrest in 40 years). Neighborhood residents subsequently decried the behavior of migrant workers living in the area, prompting the government to build dormitories with more attached facilities so that workers would not have to venture into areas where Singaporeans live. “Dormitory-based provision shops, especially if reasonably priced, could also encourage some workers to stay at their dormitory rather than travel out to a congregation area,” said a 2014 investigative committee report. Now, seven years later, these dormitories have become epicenters of Singapore’s COVID-19 crisis, validating early – and unheeded – warnings from NGOs and healthcare experts that they can easily become hotbeds of transmission.

客工的宿舍生活?

How Do Migrant Workers Live?

在新加坡,大約三十萬名客工都住在宿舍裏,一部分是專爲他們設置的宿舍,還有一些是工地上的臨時宿舍。宿舍條件十分惡劣,空間小、不通風,而一般都會有十幾名客工擠在這樣的房間裏。由于宿舍裏沒有配套廚房,客工們也沒有時間做飯,他們通常會買盒飯吃——工資的四分之一換來的是缺乏營養和衛生安全保障的飲食。辛苦而危險的工作加上糟糕的居住條件——幾乎令人難以想像在新加坡這樣一個發達的國家,還有人過著這樣的生活。

Approximately 300,000 migrant workers are split between Singapore’s 43 mega-dormitories, 1,200 factory-converted dormitories, and temporary living quarters on construction sites. Their rooms—which often house over ten people—are sometimes unsanitary and poorly ventilated. With neither kitchens nor time to cook, migrant workers pay a substantial amount of their salaries for catered food that is often spoiled and lacking in nutrients.

客工宿舍(圖片來自網絡)

值得慶幸的是,在疫情之下,客工面臨的這些問題終于開始受到重視,並且逐步得到改善。政府承認了自己的疏忽,越來越多的新加坡人也開始了解客工,並爲他們的權益行動了起來。當然,偏見仍然存在。4月13日聯合早報(新加坡的主要中文報紙之一)上的一篇社論仍然將疫情的二次爆發歸咎于客工們不良的衛生習慣和生活習性。這篇文章隨即引起了軒然大波,新加坡內政部部長也直接站出來批評這種充滿偏見的言論。這樣強烈的社會反響體現出輿論的轉變:新加坡的主流社會已經不能接受狹隘的仇外心理。當然,輿論變化是否能夠帶來切實的行動仍然有待觀察。

Nevertheless, with greater social awareness and media coverage of their plight, the situation for migrant workers has started to improve. The government has acknowledged its initial oversight, and many sympathetic Singaporeans have been galvanized to help. Of course, prejudice still exists: for example, an April 13 letter to the Editor published in Zaobao, Singapore’s most popular Chinese-language daily newspaper, blamed the COVID-19 outbreak on migrant workers’ personal hygiene and cultural habits. However, the storm of criticism this incited, including comments from Minister for Home Affairs and Law K. Shanmugam, suggests that mainstream opinion no longer tolerates such xenophobia. Sentiment on the ground does indeed appear to be shifting, although whether this will last beyond the current crisis remains to be seen.

原本8人一間的客工宿舍,由于疫情改爲3人一間(圖片來自網絡)

部分客工被疏散至更爲寬敞的居住場所,例如圖中的軍營(圖片來自網絡)

客工,不單單是新加坡的問題

A Worldwide Problem

這次的疫情不僅給新加坡人上了重要的一課,也給其他許多存在客工問題的社會帶來了巨大的影響。在德國,東歐勞工工作的屠宰場由于衛生條件差和擁擠導致了上百人的疫情爆發(例:德國600多名屠宰場工人確診);在泰國,許多來自緬甸、老撾和柬埔寨的客工因疫情丟了工作又回不了家,陷入進退維谷的境地(例:泰國外籍勞工怎麽辦?);沙特和阿聯則直接遣返了大量來自埃塞俄比亞的勞工(例:埃塞政府不再向中東的埃塞公民分發現金援助)。對于客工而言,他們既得不到外國政府的福利保障,也無法指望自己的國家能成爲疫情之下的避風港;面對疫情,他們沒有工作、沒有補助、沒有社會的關心,孤立無援,束手無策。

Looking beyond Singapore, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the plight of low-wage migrants around the world, many of whom lack basic rights, healthy living conditions, and access to quality healthcare. In Germany, cramped, squalid living quarters and overcrowded buses used to ferry workers might have contributed to the infection of hundreds of Eastern Europeans working in abattoirs. Countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have deported Ethiopian workers by the thousands over COVID-19 concerns. In Thailand, thousands of migrant workers from neighboring Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia found themselves stranded without employment or aid when the government closed all of its borders to inbound and outbound travel. Because most social welfare measures are linked to permanent places of residence, migrant workers could not access aid to purchase daily necessities. With no work or food, thousands walked home – sometimes more than 1000km. Many died of heat, hunger, fatigue, or road accidents.

圖片來自網絡

客工的問題同時也折射出了全球化的雙面性。客工現象是人力資本在全球化浪潮中重新配置的表現之一,這一群體爲各國的經濟增長作出了巨大貢獻,卻並沒有享受到與其貢獻匹配的回報。客工遭遇的困境以及疫情的蔓延這類全球性挑戰對各國在全球化時代的治理提出了新的要求。希望這次疫情所激起的社會關注不會隨著時間又一次消失殆盡,也希望這種關注能夠促進社會各界加強對客工這一群體的了解和重視,促使決策者制定更加公平的勞工政策。

The migrant worker crisis also reflects globalization’s double-faced nature. The very existence of the migrant worker phenomenon is itself a result of the global redistribution of human capital, which has created communities that have made extraordinary contributions to the economic development of each country they appear in. However, many have not managed to reap the rewards of their sacrifices. The plight of migrant workers and the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic are interconnected global challenges that present new governance issues for all countries. We can only hope that the collective attention the pandemic has drawn to migrant worker communities will outlast the current crisis, and will result in a renewed commitment to ensure equitable treatment for those who build and maintain the very foundation that cities like Singapore stand upon.