尹坤 YINKUN

1969 生于四川

1992 畢業于阿壩師範美術系

1994 北京圓明園畫家村創作,

1998年到宋莊工作生活至今。

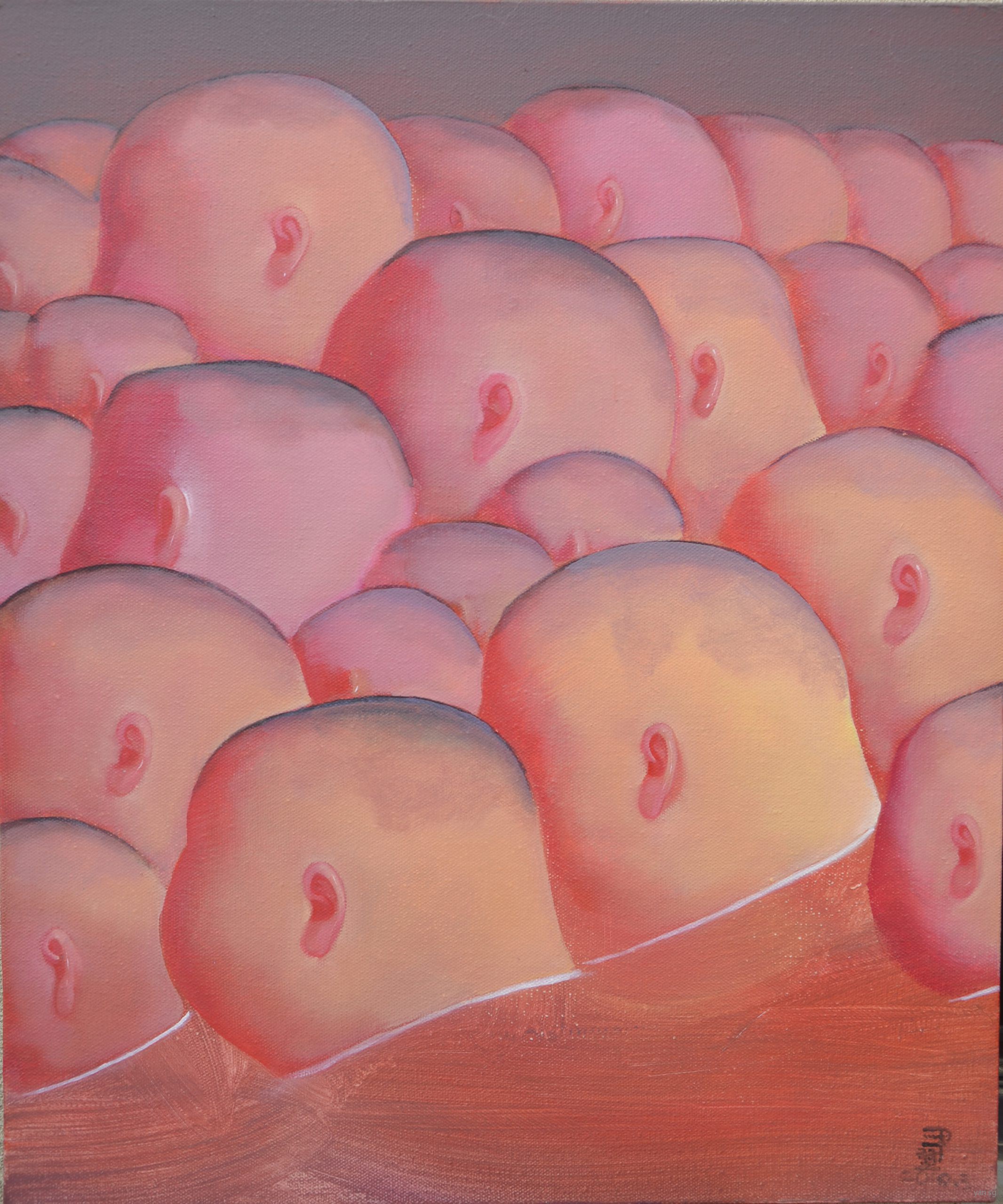

尹坤的作品承載著一定社會的元素,不僅是他自己生存的某種表現。

而在現代高科技和商業化時代,他們被描繪成中國寶貝的過程本身就帶有諷刺和荒謬的色彩,這些作品實際上反映了尹坤精神上無法“成長”的本性,他也試圖以批判的態度對待現代現實和過度商業化。

在他開發的“中國童話 — 英雄和中國寶貝”系列中,作品反映出的曆史背景和價值評判,追溯其背後的諷刺的社會起源,總耐人尋味。

Comic books or comic strips are sequence of drawings that tells a story. In China, they are called children’s book and are intended for the children who will make sense of the content of the books by looking at the series of images depicted. With the dawning of the computer and internet age, images such as cartoons and caricatures are spreading in large quantities and as a result the visual icons that children enjoy are richer than ever before. However, before the information age, the visual enlightenment children received were largely dependent on comic strips or, the so-called children’s books. Although prepared for children, they are nonetheless dominated by the spiritual dominance of adulthood and thus are intertwined with far too much adult will that is embedded in them. As a matter of fact, comic books popular on the Chinese mainland in the 1960s and 1970s are rich in strong ideological colorings. For instance, they tried to differentiate between good guys from bad ones; and on top of positive characters are added glowing, bright colors and they are seen as tall, big and full. While negative characters are presented like escaping rats etc. These are characteristics of the prevailing ideology then, i.e. set against the social background of class struggles. With such ideological influences, children’s worldly views were shaped in two dimensions only in that they saw things in an absolute way: good or bad, evil or righteous, right or wrong. Under such circumstances, they abhorred bad eggs, admired and emulated heroes, with their psychological behaviors having been overshadowed in a special way, which they could not shake off in life.

Yi Kun’s “Heroes” series were derived from such kind of psychological backdrop. Born in the late 1960s, Yi Kun spent his childhood amidst the most vehement class struggles. Although a mere child with no judgment on the merits of the ongoing struggles, Yi Kun was not immune to what was going on. Affected by the adult world and inspired by comic books, he was involuntarily involved in the vortex of class struggles and had amassed certain cultural memories of that typical age. That became the direct precursor of his subsequent series of “Heroes”. The Chinese like to call this kind of phenomena “yin guo” or “cause and result”. In post-modern life, a more obscure term has come to replace yin guo: metaphor. No matter what it is termed, be it “yin guo” or the post-modern “metaphor”, it attempts to expound a result attributable to events of the past. In fact, artistic creation has in it varied metaphors, most of which are associated to a varying extent with personal feelings and experiences. As for Yi Kun, we have no doubt judging from his current series of works that he was a big fan of comic strips and being such has had played loads of emulation games such as “fighting the landlords”, “capturing the spies” and “on the battlefield and march forward”. Certainly, had he not remembered the episodes by heart, he would not have had the opportunity to reconstruct them on paper after so many years.

Doubtless, reality can not possibly be restored and causes do not necessarily lead to results. Result is the fruition of cause but, more often than not, it is dependent on the nourishment of the environment. The environment changes everything and can even result in interactions with memory, which also coincides with post-modern theories, i.e. the referable and the referred. The referable is a kind of cause and the referred is the result which not only includes the cause but also its impact and conversion. In fact, many art works in contemporary Chinese art that deal with historical issues all share this feature. For example, the appropriation of Cultural Revolution icons by the political pop is not a mere revivification; rather it is a conversion and a new appreciation of the past from today’s view point. The “Heroes” series by Yi Kun could be associated with such characteristics mentioned above as they stand for the transition of an era. In such volatile fluctuation and revolution of the value system, Yi Kun looks back at heroes of the past age through art but he does not try to return to the past; rather he is reopening the sealed memory of history, so as to relocate the lost virginity.

To some extent, Yi Kun’s art concept is influenced by some political pop trend of thoughts such as the irony and humor of the art language. However, these are only influences. Fundamentally, Yi Kun’s art is still different from political pop. One of the differences lies in the fact that political pop has in it socialized flirtation and interpretation of political ideology, which Yi Kun’s works do not have. What they do have is children’s joy or in other words the comic book spirit that is gradually being lost in the race with time. In fact, before the “Heroes” series, Yi Kun had started experimenting with a number of artistic styles such as boys and girls playing together, and video camera lens being boosted by soap bubbles etc. The youth motifs that these styles have at the very outset reflected the artistic pursuit of the artist: he wanted no social critique but rather the reconnaissance of the youth vigor and of the pleasures of childhood. That was in fact what he wanted to achieve through his “Heroes” series. The reason for his using the perspectives of comic books to reorganize his paintings was to deprive the heroic, severe images that are typical of heroes of their revolutionary background, and to reinvigorate them with a playful atmosphere like that of a game. The reason does not stem from his admiration for the heroes of the past, rather it is to recall the spirit of the heroic era, or in practical terms to revisit his own childhood.

In his “Heroes”, the heroic characters that we used to be well acquainted with have been ridded of their revolutionary spirits, these include such heroes as Li Tiemei, Jiang Jie, Qiu Shaoyuan, Huang Jiguang, Yang Zirong, grassland heroes and heroines etc. They have become characters of the fairy tales. These changes comprise of the core of the language of Yi Kun’s artworks and they have provided a linkage with the value system of the young as well as give the artworks a historical depth and touch. History often is presented as changeable and things do not last in that they are valid only for a limited period of time and then change form after that. This is the result of the breakdown of the value system. However, if we assume that history is a long and winding river, then no matter on which side of the river, you will only experience a transit period of history. Only through living in a temporal phase in life can we really acquire the full meaning of life and avoid going towards void and imprudence. I think that what Yi Kun does through art is possibly to link the value systems, to serve as a logical bridge or fastener between the disconnected value systems. Only through being equipped with such a logical fastener can the breakaway of history be rescued from sinking into cognitive despair, resulting in the loss of the spirits. Through the fastener, the young can unlock the mystery of history and appreciate the past; while those who have gone through that lapse of history can free themselves from the chains of it and enter into a new phase with hope and promises that shine ahead of us.

(At Tongzhou District, Beijing, April 10, 2007)

展覽詳情如下:

Exhibition Dates:

22 Feb to 22 Mar 2020

11am – 6pm Monday — Saturday

At: Nanman Art

19 Tanglin Rd, #03-54 Tanglin

Shopping Centre Singapore 247909

Tel: +65 67379168 / 83577781

Email: [email protected]

www.nanmanart.com